Wikipedia:Reference desk/Archives/Science/2010 July 13

| Science desk | ||

|---|---|---|

| < July 12 | << Jun | July | Aug >> | July 14 > |

| Welcome to the Wikipedia Science Reference Desk Archives |

|---|

| The page you are currently viewing is an archive page. While you can leave answers for any questions shown below, please ask new questions on one of the current reference desk pages. |

July 13

[edit]The bends and pressure

[edit]When somebody enters an area with higher of lower pressure, does the pressure inside her/his body change as well? 74.15.137.192 (talk) 03:01, 13 July 2010 (UTC)

- Unless this is a trick question, i think the answer would obviously be yes. That's why you don't cave in or blow apart, up to a point. It's when you can no longer equalize the pressure with your environment that one of those two things might happen. Vespine (talk) 05:10, 13 July 2010 (UTC)

- This subject is complicated, so if you want more details please ask. The pressure changes somewhat. In a liquid and a solid pressure has little effect, but in a gas pressure presses the atoms closer together. Note: this is only an approximation. So if a person goes into an area of lower pressure nothing much happens to the liquid that makes up the body. Officially the pressure is lower, but practically speaking there is no change. Except for the air in the lungs - but that air equalizes with the air outside. There is one caveat, at lower pressure liquids boil easier (vapor pressure). So in a low pressure environment the liquid might try to boil. When a liquid boils the pressure goes up, which will try to stretch the blood vessels (for example). But the blood vessels refuse to stretch (somewhat), which will result in a higher pressure inside the blood vessels than in the air outside. Which is why I said somewhat - the pressure is lower, except if it's low enough to cause water to boil, in which case the body will prevent it, and will end up with a higher pressure than outside. Another change with pressure is gas solubility. Gases dissolve in water (like seltzer), the higher the pressure, the more they dissolve. Going from regular pressure to vacuum, there is little change. But at high pressure a lot of gas might be dissolved in the blood. If a person goes to an area of lower pressure, that gas will come out, and it's too much pressure for the blood vessels to prevent. Ariel. (talk) 06:09, 13 July 2010 (UTC)

iPhone 4 antenna

[edit]So it's largely confirmed that bridging the lower left gap on the new iPhone reduces the cellular signal strength by around 20db, but as an electronics engineering student 20db seems to be a lot to me, especially after spending a lot of work building a 12dbi UHF antenna. Will changing the geometry of the antenna really cause such a substantial drop in antenna gain, or is there another reason behind it (interaction with the human body/ with WiFi)? --antilivedT | C | G 03:25, 13 July 2010 (UTC)

- [1] and [2] (see all blog entries)--mboverload@ 03:55, 13 July 2010 (UTC)

- Yes I already know that the antenna gets detuned due to the hand bridging the gap, but I'm wondering will a detuned antenna really drop the signal by 20dB (that's a 100-fold reduction in RF power), or is there some other factor too? --antilivedT | C | G 04:20, 13 July 2010 (UTC)

- The iPhone4's antenna wraps around the case with a small gap. When you bridge the gap, you're effectively shorting out the antenna completely. If you have one, then at this point, your best bet is probably to buy a soft case for the phone. SteveBaker (talk) 14:43, 14 July 2010 (UTC)

- Yes I already know that the antenna gets detuned due to the hand bridging the gap, but I'm wondering will a detuned antenna really drop the signal by 20dB (that's a 100-fold reduction in RF power), or is there some other factor too? --antilivedT | C | G 04:20, 13 July 2010 (UTC)

Electrophoresis

[edit]Hi, A while ago an idea occurred to me about separating ions in an aqueous solution, but I wasn't sure if it would work or what would happen and haven't found much information since then either so I thought I'd ask here. Basically what I was thinking was, if you had a ionic solution - say salt water - and if you applied an electric field, then the +ve ions would move in the direction of the field and the -ve ions would move opposite to the field, until that movement created an equal and opposite field. So in the brine, if put two parallel metal plates on either side of the solution (insulated from it of course) and applied a voltage across them, then the Na and Cl ions would move slightly towards -ve and +ve plates respectively. Now if you put a solid partition down the middle of the set up and removed the field, you'd have a one solution with a slight excess of sodium ions and a another with a slight excess of chlorine ions.

My questions are: would it work at all? And if so, what would the properties of the created solutions be? After looking up on google and wikipedia I eventually found "electrophoresis" which seems to be what I'm thinking about, and seems to indicate that it would work; but beyond that, I can't find any more useful info - mostly just stuff about seperating DNA and whatnot, leaving my second question unanswered. The kind of stuff I'm wondering is, for example, what would happen if you tried to evaporate the water? Would the ions evaporate too? Or what if you dipped a positively charged plate into the solution with excess chlorine? Would the excess ionic chlorine then lose electrons and turn into chlorine gas??

202.37.61.14 (talk) 03:48, 13 July 2010 (UTC)

- Are you certain they would actually move? Because water is also ionic, and the H and OH groups should also separate, but obviously they don't. I think you need energy input to separate the ions, an electric field is not enough (unless you were somehow taking energy from it, in which case it would do the same as electrolysis). Ariel. (talk) 06:36, 13 July 2010 (UTC)

- I wouldn't bet money that they would move, but I can't see why they wouldn't - the energy input would come from the transient (displacement) current that would flow when you introduce the field, in the same way as energy is stored in a capacitor even though, once you've charged it, no current flows and no energy is transferred. As for the water, I suppose it would also move, but I'm assuming that it would only rotate, with most of the movement happening with the ions (since I guess it'd take less energy to move the ions than break the covalent bonds of the water, in same as that when you perform the electrolysis of brine it's the salt rather than the water that comes apart). 202.37.61.14 (talk) 07:29, 13 July 2010 (UTC)

- If you pass a current through the cell rather than just apply an electric field, you end up with a brine cell used in the chloralkali process. This makes sodium hydroxide and chlorine gas. Brammers (talk/c) 07:37, 13 July 2010 (UTC)

- Yeah, I know, but I wasn't talking about electrolysis; in fact the whole notion entered my head when I wondered what would happen if you could avoid the oxidation and reduction that happens in electrolysis. 202.37.61.14 (talk) 10:26, 13 July 2010 (UTC)

- 202.37 is correct as far as what we're describing here is, effectively, a capacitor, with an (insulated) bag of saltwater acting as the dielectric between the plates. Now, what happens when you apply an electric field across our bag of saltwater? The saltwater solution will become polarized, arranging itself (as the original question notes) opposite the appplied field. How does that come about? There are a few possibilities. 1) The sodium and chloride ions can migrate to generate a charge gradient across the solution. 2) The water molecules can ionize, generate a large pool of free hydrogen/hydronium and hydroxide ions which can migrate. (The very small population of these ions naturally present near neutral pH is also able to migrate.) 3) The water molecules orient themselves so that their existing dipoles align. 4) The molecules in solution become individually polarized — induced dipoles are generated by distortions to each molecule's (or atom's) electron cloud.

- In practice, (4) is a very fast process, and (3) is quite quick too. (1) requires movement of ions over distances which are large (for molecules) and would be rather slow. I suspect it also has a heavy entropy penalty, and so is thermodynamically less favorable. (2) requires ionization of water and is probably quite energetically costly — so also unlikely to make a significant contribution unless the 'cheaper' processes have been exhausted. While I haven't done the math, my gut instinct here is that induced dipole formation and dipole orientation will be responsible for the vast majority of the polarization of the sample, and you won't see significant ion migration and separation until you get very close to the breakdown voltage of the dielectric. TenOfAllTrades(talk) 13:45, 13 July 2010 (UTC)

A very tiny amount of charge separation will prolly occur. This is because separating as much as 0.000000000000001 mol of Na+ and Cl- (probably smaller) over that distance will result in a HUMONGOUS field that will cancel out the previous field.

Now, that sort of charge separation is so unstable, so with lots of mutual Na+ repulsion and mutual Cl- repulsion, Na+ stops becoming an inert counterion and becomes Lewis acidic, generating a proton gradient, which will travel over to the chloride-dense side. Meanwhile at that density, the chloride ions will actually start to become basic. Part of this is due to Coulombic forces, part of this is due to the entropy considerations (so much charge separation ==> lots of water ordering). You'll end up making HCl and NaOH, or possibly NaOH, Cl2 and H2.

Bear in mind when you separate DNA, you aren't just moving the negative part of the DNA... the counterions travel with them. John Riemann Soong (talk) 15:11, 13 July 2010 (UTC)

help

[edit]I am creating a page on my school from where I graduated 3 years ago. I have all the required data needed but do not have a website of reference since the school itself does not have one. Can I still continue with my article?—Preceding unsigned comment added by Nepalsk (talk • contribs)

- The best place for this question would be at the Help Desk. They answer questions about how to edit Wikipedia there. This is the Reference Desk where we answer questions about things outside of Wikipedia. Dismas|(talk) 05:48, 13 July 2010 (UTC)

- Have a read of Creating a new page. There are thousands of schools in the world, do they all really need a encyclopedia article about them? If the school in question doesn't have a website, and you are struggling to find any references, it could be that the school is simply not notable enough to warrant its own article. Why should the school have a page? Don't take it personally but if the only answer you can think of is because you graduated from it, I'm not sure that's a valid enough reason. Vespine (talk) 05:52, 13 July 2010 (UTC)

- If you were in the UK, you'd be able to find Ofsted reports on the school online, as well as potential menions in local history books if it's been around a while. Is there an equivalent of Ofsted reports available in the country in question? That would ensure at least some sources. 86.164.57.20 (talk) 14:00, 13 July 2010 (UTC)

- Have a read of Creating a new page. There are thousands of schools in the world, do they all really need a encyclopedia article about them? If the school in question doesn't have a website, and you are struggling to find any references, it could be that the school is simply not notable enough to warrant its own article. Why should the school have a page? Don't take it personally but if the only answer you can think of is because you graduated from it, I'm not sure that's a valid enough reason. Vespine (talk) 05:52, 13 July 2010 (UTC)

- You should read our guideline: Wikipedia:Notability (high schools) which lays out the rules for writing articles about schools - and contrary to what User:Vespine said, we do generally accept articles about high schools without being too concerned about notability. SteveBaker (talk) 14:39, 14 July 2010 (UTC)

- Well you learn something new every day:) Thanks for the correction steve.. Vespine (talk) 22:47, 14 July 2010 (UTC)

- For what it's worth, I thought the answer would be "No, you may not write about your high school" too! But I thought I'd find the official guideline and quote what it said - and it's just as well I did! Amazingly (to me), all high schools are now automatically considered notable. That certainly wasn't always the case because not long ago I had to fight off an RfD for my Alma Mater Chatham House Grammar School - in my case it was easy because Chatham House is the oldest government-run school in the UK and Sir Edward Heath (one time Prime Minister of the UK) was a fellow "Old Ruymian". I figured that if a school like that has to fight to be considered notable, most other schools would have no chance! But it looks like the policy has changed...which (IMHO) is a good thing. SteveBaker (talk) 23:22, 14 July 2010 (UTC)

- Well you learn something new every day:) Thanks for the correction steve.. Vespine (talk) 22:47, 14 July 2010 (UTC)

Is HGH a precursor to testosterone?

[edit]My friend says HGH is a precursor to testosterone. I did a search online and I can't find anyplace that says that. Is it? —Preceding unsigned comment added by 76.169.33.234 (talk) 06:18, 13 July 2010 (UTC)

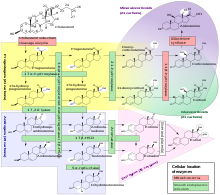

- It doesn't seem to be. The picture I linked shows that it starts from cholesterol. The article on HGH does mention that the production of HGH is stimulated by androgens (like testosterone), but not the reverse. Ariel. (talk) 06:31, 13 July 2010 (UTC)

- No, HGH is not a precursor to testosterone. HGH is a polypeptide (well, actually a group of related polypeptides). Testosterone is a steroid, derived from cholesterol. Axl ¤ [Talk] 10:22, 13 July 2010 (UTC)

Can you 'boil' heat water by compressing it?

[edit]A gas heats up when compressed. I assume the same happens with a liquid. Now I know water is hardly compressible, so a huge lever would be needed, so to say, but it seems to me that that should be possible. But how far can you heat it up? What happens when it gets to the boiling point? It can't boil in the normal sense because it can't evaporate. This article says it forms a solid at 100 C (= 212 F). But is this practically feasible, with relatively everyday materials? What sorts of pressures would be involved? Several articles I found mention 'diamond anvil cell techniques', but how far could this be taken with a normal strong container, say a diving cylinder? DirkvdM (talk) 08:26, 13 July 2010 (UTC)

- Have you come across a kitchen appliance called a pressure cooker? It cooks food in water in a heated sealed "cooker", taking advantage of the fact that the pressure of the steam raises the boiling point of the water. HiLo48 (talk) 09:00, 13 July 2010 (UTC)

- On a side note, I can remember going to a science museum when I was a child, where they had a demonstration of the changing boiling point of liquids with pressure, in which a glass of water was sealed inside a chamber and an hydraulic system was rigged up so that when you pulled a knob the pressure in the chamber dropped dramatically, causing the water boil; so the opposite is certainly true - you can boil water by decompressing it, so to speak. 202.37.61.14 (talk) 10:14, 13 July 2010 (UTC)

- (After edit conflict with Dr Dima below)

- Yeah, I thoght about those two, but they're fundamentally different.

- In a pressure cooker the pressure is the result of the heat. What I want is the reverse, produce heat as a result of pressure.

- The goal is not to boil (evaporate) the water, but to heat it up. My mistake, I shouldn't have used the word 'boil'. Which is why I changed it into 'heat'.

- But what I really want to know is if this can be done 'at home', or at least with simple materials, outside a laboratory environment and certainly not using diamonds. DirkvdM (talk) 10:49, 13 July 2010 (UTC)

- Thermodynamics is not all intuitive. This is a great example. You can bring liquids to "boil" (I'll explain the quotes in a minute) both by compression and by expansion. -- 1 -- . Let us first consider expansion. Expansion is easy: drop the pressure below the vapor pressure for the given temperature of the liquid, and the liquid will start to boil. This is what 202.37.61.14 just described. If you keep pressure and temperature constant, the liquid will all boil out. If you do not keep temperature constant (do not provide heat source) but keep the pressure constant, the liquid will cool as it boils, and eventually stop boiling. This will happen when the vapor pressure -- as a function of temperature -- drops enough to match the value of the pressure that you maintain. If the pressure is maintained below the solid-liquid-gas triple-point pressure, the liquid will turn into mixture of solid (ice) and gas (vapor). -- 2 -- . Let us now consider compression. Compression is more tricky. As the OP said, liquid is heated when compressed. When the heat can escape, the compressed liquid will eventually turn into solid. However, when the heat produced has nowhere to escape, you end up raising both the temperature of the liquid (that is, the vapor pressure) and the boiling point (that is, the vapor pressure needed for the vapor bubbles to form). This competition is decided by a number of factors. The most important one is how you compress. If you compress gently (isentropically), the heating is weaker than when you compress violently (by a shock wave). I do not know if you can produce a liquid-gas mixture by sending a shock wave through water (no rarefaction, just shock); but you can definitely bring the water above the liquid-gas critical point. Above the critical point you cannot tell the liquid from the gas, so "boiling" has no meaning. If you allow the liquid to isentropically expand after the shock and to return to the original pressure, its temperature will end up higher than the initial one, and it may well boil. Finally, an extremely strong shock will turn liquid into plasma, which is essentially an extremely hot gas (so hot that some or all electrons leave the atoms and become free). So yes, you can turn the liquid into gas by either expanding it or compressing it; but you need to know how to compress or how to expand. --Dr Dima (talk) 10:29, 13 July 2010 (UTC)

- Ah yes, I should have also mentioned that the heat is not allowed to escape (although that is somewhat inherent to the question), so a diving cylinder is inside a thermos flask, so to say.

- And again, apologies about the use of the word 'boil', because that is not what I'm after. (Note, though, that I also put it between quotes, for just that reason). I want a rise in temperature, but by a considerable amount, not just a few degrees.

- What I was thinking about is a gradual build-up of the pressure. But as I understand your last bit (which I don't fully), that is really about a shock wave. I was thinking more about something like cranking up the pressure by hand, with a lever.

- Also, I was assuming there is no air in the container, just water. However, a small amount of air would be unavoidable in practise, and since that is (relatively) highly compressible, it would affect the process considerably, I suppose. But wouldn't it at some point be 'absorbed' by the water? So here's an added question. How much would all this be affected by any air in the container? DirkvdM (talk) 10:49, 13 July 2010 (UTC)

For not too large pressures, you can calculate this using the heat capacity and the coefficient of thermal expansion as follows. Since in this process no heat is exchanged with the environment, the entropy stays constant (assuming you compress it slowly). The differential of the entropy in terms of dT and dP can always be formally expressed as:

If we put dS = 0 and solve for the ratio dT/dP, you get the partial derivative (dT/dP)_S which tells you by how much the temperature will rise per unit pressure increase. However, using the above expression, you will get an expression involving the entropy. The coefficient of dT can be expressed in terms of the heat capacity a constant pressure:

To simplify the other coefficient, consider the fundamental thermodynamic relation

You can read this as T being the partial derivative of E w.r.t. S at constant V and minus P being the partial derivative of E w.r.t. V at constant S. The second derivative of E w.r.t. S and V can be evaluated by differentiating w.r.t. S at constant V first and then by differentiating w.r.t. V at constant S, or the other way around. The equality of the two ways of evaluating the second derivative yields that the derivative of T w.r.t. V at constant S is the same as the minus the derivative of P w.r.t. S at constant V.

Now, we want an identity involving the derivative of S w.r.t P at constant T. We can find that by partially integrating both terms in the fundamtal thermodynamic relation

So, we have

where G = E - T S + P V is the Gibbs free energy.

And then the symmetry of the second derivatives of G yields that

We can thus express this in terms of the thermal expansion coefficient

Putting everything together, you find that

where lowercase c_P is the specific heat capacity per unit mass and rho is the density.

Count Iblis (talk) 15:26, 13 July 2010 (UTC)

At 25 °C and 1 bar, you find that this is approximately 1.48 *10^(-3) K/bar. So, you can see that you need to raise the pressure to thousands of bars to get just a few degrees of temperature increase. You can't then use the above linear formual anymore, of course, as the density and expansion coefficients will change. But it is still a good order of magnitude estimate. Count Iblis (talk) 16:03, 13 July 2010 (UTC)

- Ah, thanks. I don't follow most of your first post (largely because I don't know what the symbols stand for), but the linear equation at 25 C is within my grasp. :) To increase the temperature just one C (or K), to 26 C, would require about 700 bar. That's 70 million Pa. Which is 70 million kg/m*s2. For 1 l = 1 kg of water that would mean .... excuse my continued ignorance, but how do I translate this into energy? And does that become more or less as the pressure and temperature increase? The density barely changes, and I assume there is hardly any thermal expansion and I further assume the two are inversely related. Or something. That's about as far as I get. Help! DirkvdM (talk) 17:23, 13 July 2010 (UTC)

- You can use the fundamental thermodynamic relation

- dE = T dS - P dV

- and use that dS = 0. Put differently, because this is an adiabatic process, the work done on the system is the change in internal energy. It is convenient to express dV in terms of dP and dS:

- If you substitute this in the fundamental thermodynamic relation and then put dS = 0, you find that the energy change is:

- where is the isentropic compressibility. Now this can be expressed in terms of the isothermal compressibility and the heat capacity ratio, as derived in the article relations between heat capacities:

- You can easily find the isothermal compressibility in tables. As explained in the same article, the specific heat capacity at constant volume can be expressed as:

- So, we have:

- All the quantities in this equation can be easily found. If we approximate things by assuming that stays constant as the pressure is increased (this should not be too bad an approximation), then integrating the equation for dE_{adiabatic} gives for the energy increase per unit mass:

- So, it is proportional to the change in the square of the pressure. But you can compute things precisely by doing a numerical integration using tabulated values for the thermal expansion coeffcient, the isothermal compressibility and the density, if you also consider the equation for the temperature change derived above.

- With only my half forgotten secondary school physics and math, I'm hanging on by my fingernails here. :) In the first equation, the change in energy, which is the energy one has to put in, is related to T, P and V, being temperature, pressure and volume, and S, which I now understand stands for mass, which indeed does not change, so dS=0. So in the second equation the first part after the equal-sign is 0, so it says the acutal change in volume is the change in volume per change in pressure times the actual change in pressure. That makes sense to me. But after that, I don't follow.

- So let me skip to the final formula. Rho is density, which is mass per volume. For water, that is 1 kg/m3. is the isentropic compressibility. The compressibility article mentions this for water at 25 C (although I don't know if that's isentropic - I barely even know what that means): 4,6 * 10-10 m2/N = 4,6 * 10-10 m*s2/kg. For 1 C temperature change we found above that that requires a pressure change of 7 * 108 Pa = 7 * 108 kg/(m*s2). Fill all that in in the formula and we get

- (4,6 * 10-10 m*s2/kg * (7 * 108 kg/(m*s2)2)) / (2 * 1 kg/m3) =

- (4,6 * 72)/2 * 1016-10 ((m*s2/kg * kg2)/(m2/s4)) / (kg/m3) =

- 113 * 106 m2/s2

- Hold on, I should have ended up with kg*m2/s2. My head is spinning slightly. I can't even read my own equations anymore. :) Where did I go wrong? DirkvdM (talk) 10:49, 14 July 2010 (UTC)

- I find 1130 J/kg. The pressure is 700 bar = 7*10^7 Pa and the density is approximately 10^3 kg/m^3 (more precisely 997 kg/m^3). The cpompressibility is the isothermal compressibility, but the correction term you need to subtract to compute the isentropic compressibility would change it by a few percent and the value for the compressibility isn't that accurate to start with.Count Iblis (talk) 16:24, 14 July 2010 (UTC)

- S does not stand for mass but entropy, [Introduction_to_entropy]. Entropy is a somewhat obscure quantity, it measures the randomness of the system, it is greatest when everything is mixed and has the same temperature.

- It can never decrease in a closed system (without external influences temperatures are smoothed out and things are mixing together).--Gr8xoz (talk) 07:09, 15 July 2010 (UTC)

- Oh dear, yes, of course, it's J/kg, which is indeed m2/s2. All the calculating got in the way of logical thinking, I suppose. :)

- And 70 million is indeed 7 * 107, not 7 * 108. That was an error in an earlier post. Since that is squared, it brings the result down a factor 100. And of course density is (approximnately) 1 kg/L, which is 1000 kg/m3. Which brings it down a factor 1000 and I end up with your result.

- So it's 1130 J/kg (or thereabouts). That's not bad at all. A human body can generate a few hundred watt of power, which means it would take just a few seconds to get 1 L of water to heat up 1 C. That's assuming 100% efficiency, so it'll be more like half a minute in practice.

- This again raises the question how this value changes as the pressure rises. If it were linear, then it would take something like half an hour to get 1 L of water to a temperature where one could use it to cook a meal. Without fire! Although it would start to cool down again immediately (though less so if it stays in the thermally insulated container), but then again, one can raise the temperature even further, which is not possible with heat in a normal (open) cooking pot. It's a lot of work, but in certain circumstances, therre might be a practical use for this. DirkvdM (talk) 06:16, 15 July 2010 (UTC)

Nitroglycrine

[edit]What is the safest and most practical method to make Nitroglycrine ? —Preceding unsigned comment added by Jon Ascton (talk • contribs) 10:41, 13 July 2010 (UTC)

- This may come across as sarcastic, but the best way is not to make it. It is a highly dangerous explosive formed by a reaction between highly dangerous acids and glycerin. Just the heat of the reaction, if uncontrolled could explode it sending you flying. C-4 is a much better explosive, if you drop it on the floor it won't blow up. It needs a detonator like lead azide or mercury fulminate to detonate it. Gunpowder is also useful. Armstrong's mixture is a highly sensitive explosive made from easily obtainable materials. CuO-Al thermite is a low explosive, but it is difficult to ignite. --Chemicalinterest (talk) 10:51, 13 July 2010 (UTC)

- Not those established users doing tests again, I hope. Hopefully not a fight about renaming titles. --Chemicalinterest (talk) 10:52, 13 July 2010 (UTC)

- I've signed the post Nil Einne (talk) 11:12, 13 July 2010 (UTC)

- Ok, then tell us how to make C-4....

- Not those established users doing tests again, I hope. Hopefully not a fight about renaming titles. --Chemicalinterest (talk) 10:52, 13 July 2010 (UTC)

- (EC) Have you looked at Nitroglycerine#Manufacturing? It covers the industrial angle. I don't think it's common for people to produce it for fun, because of the obvious risks. The Bojinka plot evidentally used nitroglycerine but I don't think it's a particular common explosive of choice for terrorists and such either. Nil Einne (talk) 11:19, 13 July 2010 (UTC)

- Nitroglycerin is easy to make. All you need is college-level chemistry. From there, find some idiots to test your procedures at different temperature levels until you get it to work without exploding. Then, if you have and IQ over 10, which would mean that you aren't stupid enough to waste your time trying to make a weak explosive like nitroglycerin when there are much stronger explosives that are much safer to make, you will soak paper in the nitroglycerin and roll them up to make dynamite. -- kainaw™ 12:04, 13 July 2010 (UTC)

- Hey, wait man. Didya say "weak"? I thought NG was the strongest xp around, bigger than RDX etc...

- My chemistry book states that CL-20 is the strongest chemical explosive. --Chemicalinterest (talk) 12:53, 14 July 2010 (UTC)

- Hey, wait man. Didya say "weak"? I thought NG was the strongest xp around, bigger than RDX etc...

- What makes you assume he wants a strong explosive? He just says he wants to know the safest and most pracical method to make nitroglycerine. He doesn't say why, which could be loads of reasons (although I think we can rule out homework).

- Btw, speaking of questions we are nog supposed to answer, medical questions are among them. Questions about good ways to blow yourself up seem to be ok, though.

- Here's my answer: out in some wasteland, from a safe distance. Maybe build a robot first. :) DirkvdM (talk) 14:06, 13 July 2010 (UTC)

- FYI, dynamite isn't paper soaked in nitroglycerin, but some filler/stabilizer like sawdust or diatomaceous earth soaked in it and then stuffed into a paper tube. --Sean 15:00, 13 July 2010 (UTC)

- Really? I thought it was agarose gel soaked in nitroglycerine. John Riemann Soong (talk) 15:05, 13 July 2010 (UTC)

- That might be an alternative absorbent that serves the same role in its manufacture. I was just pointing out that a stick of dynamite isn't a rolled-up tube of nitroglycerine-soaked paper, as it might appear. --Sean 15:31, 13 July 2010 (UTC)

- Several ways to make it; see dynamite. --Chemicalinterest (talk) 15:36, 13 July 2010 (UTC)

- That might be an alternative absorbent that serves the same role in its manufacture. I was just pointing out that a stick of dynamite isn't a rolled-up tube of nitroglycerine-soaked paper, as it might appear. --Sean 15:31, 13 July 2010 (UTC)

- Really? I thought it was agarose gel soaked in nitroglycerine. John Riemann Soong (talk) 15:05, 13 July 2010 (UTC)

- FYI, dynamite isn't paper soaked in nitroglycerin, but some filler/stabilizer like sawdust or diatomaceous earth soaked in it and then stuffed into a paper tube. --Sean 15:00, 13 July 2010 (UTC)

black swallowtails

[edit]i had a black swallowtail chrysalis we found in the garden and it was alive when we found it , it was wiggling, but after i kept it in a tupperware on the porch all winter and put a few drips of water on it every few days it never hatched. so we ripped it open and it was dead. what did i do wrong????? we also ad some other catterpillars, like wooly bears, inchworms, and black swallowtails and they died too. are we cursed or what?????--98.221.179.18 (talk) 12:21, 13 July 2010 (UTC)

- Speaking from having tried this with various (UK) species of butterflies and moths over a decade or so as a child/youth, it's harder than most people realise: caterpillars and pupae often need very specific foodstuffs (including the actual age and condition of the plants) and environmental conditions (like temperature and humidity) to develop to maturity, and it's not easy finding out just what these are in each case, although hobby organisations of Lepidopterists may be able to give useful advice. Try and track one down via your local library or by searching the internet.

- A general aim should be to try to reproduce their ideal conditions as closely as possible, which in the case of pupae may include burying them under a light layer of soil or pinning them up by the silk pad attached to their cremaster so as to hang down from it as they would normally, depending on the usual habits of the species concerned. It's usually better to build or obtain dedicated boxes or tanks (empty aquaria are useful) rather than using small ad hoc containers - there used to be specialist companies selling such entomological equipment; I don't know if any still operate, but if they do you could consult their catalogues to see what sort of housing has been designed. Chrysalises need to be able to breath but usually do not need to be kept artificially moistened (hence, probably, your problem with that pupa), and some benefit by being placed under gentle warmth to simulate sunshine - I remember successfully hatching a large proportion of Small tortoiseshell pupae close to maturity (when you can see the wing colours through the shell) by placing them on paper on the bottom of a large (dry) fish tank under a couple of incandescent light bulbs.

- A further difficulty is that many caterpillars and chrysalises are already diseased or parasitised when you find them. Bear in mind that in the wild most never make it to maturity for these and other reasons (like being predated by birds, which you can prevent) - otherwise we'd be up to our necks in the adults! Also, young caterpillars in particular often need very delicate handling - a common ploy is to pick them up gently on the tip of a small artist's brush rather than touching them directly.

- Watching the development of butterflies and moths is certainly fascinating. so persevere! One warning, though, make sure you're not interfering with any locally or nationally rare species, which may well be illegal and probably bad for the species - pupils at the prep school (i.e. aged 7-11) associated with my senior school (11-18) in Kent once inadvertantly but significantly reduced the population of a rare British fritillary before older naturalists caught on. 87.81.230.195 (talk) 16:03, 13 July 2010 (UTC)

Equation

[edit]I saw this equation posted on a forum: .It looks like it has something to do with angular momentum, but I've never seen it before. Can someone expain what it means? 74.15.137.192 (talk) 14:07, 13 July 2010 (UTC)

- It looks like it is something to do with relating angular momentum at different points. If would help if you linked to the forum so we can see it in context. We need to know what the variables mean if we're going to give a definitive answer (I'm just guessing at the moment based on commonly used variable names. --Tango (talk) 14:16, 13 July 2010 (UTC)

- (ec) What Tango said. dLCM/dt is the time rate of change of the angular momentum vector. ω is generally an angular velocity (rate of rotation), but in the above equation it's a vector quantity (in order for it to be crossed with the L vector). We'd be better able to put the equation in context if you provided a link to the relevant discussion. TenOfAllTrades(talk) 14:23, 13 July 2010 (UTC)

- Angular velocity as a vector means the magnitude is the usual rate of rotation and the direction is the axis of rotation. --Tango (talk) 15:55, 13 July 2010 (UTC)

- Ah, of course. My coffee hadn't kicked in yet! I'm still not certain exactly how the formula given would/should be applied, however. It looks like it might be the change in angular momentum when you apply a torque to a rotating body around some axis other than its original axis of rotation, but context would, again, be very helpful. TenOfAllTrades(talk) 16:24, 13 July 2010 (UTC)

- Angular velocity as a vector means the magnitude is the usual rate of rotation and the direction is the axis of rotation. --Tango (talk) 15:55, 13 July 2010 (UTC)

Unfortunately there wasn't really any context to it. Someone just posted it as his 'favorite equation', if that makes any sense. Personally, it doesn't make much sense to me, because if the angular momentum and the angular velocity happen to be parallel, then the second term just become zero. 74.15.137.192 (talk) 17:29, 13 July 2010 (UTC)

- If ω is the angular velocity of the reference frame s, the equation looks like it could be the torque on CM in the rotating frame. 198.103.39.129 (talk) 18:02, 13 July 2010 (UTC)

Elevated heart rate

[edit]Is it dangerous or unhealthy to have a slightly elevated heart rate for a short period of time (a couple months) from a diet medication such as phentermine in a healthy adult? —Preceding unsigned comment added by 76.169.33.234 (talk) 14:36, 13 July 2010 (UTC)

- That's going to depend on what constitutes 'slightly', what the resting heart rate is, what other medications are being taken, what other conditions or genetic susceptibilities that the patient has, and a host of other factors. Our article on phentermine lists some of the common side effects, as well as providing links to more extensive information. TenOfAllTrades(talk) 14:53, 13 July 2010 (UTC)

- (e.c.) I'm not sure we can answer questions like that. It's not a diagnosis, but answering you wrong would be bad, so it would be irresponsible to try. You can look up tachycardia though, which is the medical term for that, and has some pretty serious effects listed there - but it depends on how fast you mean by slightly. Ariel. (talk) 14:55, 13 July 2010 (UTC)

- It's not diagnosis, but it is prognosis, which is the other thing we aren't allowed to do when asked medical questions. Therefore, we cannot answer this question. A doctor, or possibly a pharmacist, needs to be consulted. --Tango (talk) 15:56, 13 July 2010 (UTC)

- A doctor should certainly be able to answer you. Vimescarrot (talk) 15:47, 13 July 2010 (UTC)

- I understand your concern about answering the question, but I'm not taking it, I was just wondering. Of course I would talk to a doctor and get a prescription first, its just I am wondering if it is dangerous even before I go see a doctor. What if no other medications are being taken, no heart problems at all with me or any family members, and with 10-20 beats per minute increase. Also I am 22 years old and need to lose about 10-15 pounds so I am not obese. Thanks again —Preceding unsigned comment added by 76.169.33.234 (talk) 17:02, 13 July 2010 (UTC)

- It isn't that people here don't want to help... it's just that what you are asking is not within the realm of what RD volunteers are capable of answering in a responsible manner. You have been given some appropriate links in the first few responses but you asked a yes/no question and, as indicated by TenOfAllTrades, there are many nuances that make it a much more complicated answer than you are hoping for. Sorry. --- Medical geneticist (talk) 17:30, 13 July 2010 (UTC)

- OK, got it. As for the other factors, I was just asking in general... I did get an answer from someplace else. Thank you to everyone for the help :-) —Preceding unsigned comment added by 76.169.33.234 (talk) 02:50, 14 July 2010 (UTC)

I dont see any risk in giving general medical info as long as we are not giving medical advice. Phentermine is an amphetamine-like prescription medication used to suppress appetite. It can help weight loss by decreasing your hunger or making you feel full longer. Phentermine may be recommended if you're significantly overweight — not if you want to lose just a few pounds. Phentermine is one of the most commonly prescribed weight-loss medications, but it does have some potentially serious drawbacks. Raised BP, Nervousness and Constipation are very common. Heart rate is not a fixed number but a range which can change with age and other factors. Even for two people in the same age group, the heart rate could be different due to other factors. You havent mentioned your age or what your heart rate is. This drug, being a prescription drug, has to be prescribed to you by your doctor and Im sure he will check your heart rate, BP and other vitals. A slight increase or even a persistent increase Im sure would be recorded by him/ her and it would be appropriate that you address this issue of occasional or persistent tachycardia with your consultant. Fragrantforever 04:34, 14 July 2010 (UTC) —Preceding unsigned comment added by Fragrantforever (talk • contribs)

Stretching tapes

[edit]why do cling films and some kind of surgical and other tapes need to be stretched in order to self-adher properly? It doesn't seem to be just geometry tension and pressure but I am struggling to work out the exact adhesive mechanism/ --BozMo talk 16:29, 13 July 2010 (UTC)

- This may not be correct, but think of the adhesive as many tiny parallel poles covered with adhesive on the sides and nonsticky on the bottoms, where they are exposed. They are mounted on the flexible backing. When the backing is stretched, it breaks down the parallel arrangement, allowing the sticky sides to come in contact with what it is adhering to. --Chemicalinterest (talk) 12:56, 14 July 2010 (UTC)

Dark matter

[edit]Here I don't see why they think there is dark matter here. All I see is a dark ring, but dark matter does not interact with light. Is there some gravitational lensing here or something? --The High Fin Sperm Whale 17:28, 13 July 2010 (UTC)

- Yes, lensing. It's mentioned in the accompanying press release. --Sean 17:45, 13 July 2010 (UTC)

Gravitation

[edit]Two bodies of equal mass 1 kg are placed 1 kilometre apart in free space.Only force acting between them is gravitational force.How to find time after which the bodies will meet —Preceding unsigned comment added by 59.92.2.26 (talk) 17:59, 13 July 2010 (UTC)

- This looks like a homework question. Have you looked at the articles Newton's laws of motion and Newton's law of universal gravitation? You don't mention how large the bodies are.

If they are each a kilometer in diameter they are touching before you start!Cuddlyable3 (talk) 18:10, 13 July 2010 (UTC)- Also important is initial velocities. If the bodies are stationary to begin with you will get very different answers than if they are moving relative to one another. --Jayron32 23:49, 13 July 2010 (UTC)

- I was kind of wondering that also. How would you get them positioned perfectly still, with no initial force in any direction? Very hard to do - almost impossible, I'd say. In effect, the question is postulating God doing it, because He can do anything. But even the most finely tuned machine is liable to have some variation in it. Maybe the teacher is hoping they won't ask that question. :) ←Baseball Bugs What's up, Doc? carrots→ 00:10, 14 July 2010 (UTC)

- Also important is initial velocities. If the bodies are stationary to begin with you will get very different answers than if they are moving relative to one another. --Jayron32 23:49, 13 July 2010 (UTC)

- They could have been placed at the specified distance in space by being tethered on a string of negligible mass which was vaporized by a laser at t=0. Certainly no initial velocity should be supposed. And what, pray tell, is "Inertial force?" The size is an interesting question. For textbook purposes, I would assume a very small radius for each mass.How would the answer vary if the objects 1 km apart were each spheres of uniform density of radius 1 mm versus 10000 km?Edison (talk) 04:42, 14 July 2010 (UTC)

- See Free-fall time, for small bodies this gives 96 years in the first case, for the second case it depends on the masses.--Patrick (talk) 06:09, 14 July 2010 (UTC)

- The masses were stated to be one kilogram. If 10000km is incomprehensibly large for a 1 kg mass, then how about spherical masses of uniform density of 1 kg mass and 1 km diameter separated at T=0 by 1 km? Edison (talk) 03:05, 15 July 2010 (UTC)

- Using Free fall#Inverse square law gravitational field: 268 years, and for diameters of 10000 km 1,480,000 years. For large diameters the time is proportional to the (equal) diameters.--Patrick (talk) 13:11, 15 July 2010 (UTC)

- The masses were stated to be one kilogram. If 10000km is incomprehensibly large for a 1 kg mass, then how about spherical masses of uniform density of 1 kg mass and 1 km diameter separated at T=0 by 1 km? Edison (talk) 03:05, 15 July 2010 (UTC)

- See Free-fall time, for small bodies this gives 96 years in the first case, for the second case it depends on the masses.--Patrick (talk) 06:09, 14 July 2010 (UTC)

Food preparation, handling of (fish) meat

[edit]Dear Wikipedia

I am surrounded by chefs and food at my workplace. Since I was employed, I've doubled my knowledge of food, fish in particular, and how to prepare it. I present to you now, or rather I ask advice on, a certain number of axioms. If anyone could please provide the scientific answers to why a chef might be inclined to do so and so, I would be most thankful. I'd hate to run around cooking and telling others to cook, without knowing the underlying scientific principles.

1) Why does meat have to rest after being cooked? Say for instance a beef is fried on pan for 6-7 minutes, then placed in the oven for 15-20 minutes, it should 'rest' (ie lie idle on a plate) approximately 10 minutes. The matter is not how long, but for what reason.

2) Is the sugary content of a meat an indication of whether or not it is good for frying on a pan? I understand to some degree the principles of the maillard reaction, but this question came up when dealing with fish: Some fish (which?) do not contain as much sugar as other, and are less subject to being fried. Haddock comes to mind as a fantastic frying fish, ditto Coalfish, whereas Trout... would that work at all?

3) Red fish filets/pieces (salmon, trout etc) can't lie flesh to flesh with white fish. Any reason?

4) To eat raw (red) meat is practically unheard of. Still whale is offered as part of our sushi. Can ordinary land-mammal meat be eaten in the same manner?

5) Some fish, especially the 'looser' ones like Cod, can not be sliced into too small pieces before being fried. This will see them fall apart, more or less. Why? Also, Haddock has a far higher tolerance, sticking more easily together during heating. What is the difference between the meat of the haddock and cod?

Thank you in advance for your time and answers :) 88.90.16.109 (talk) 18:00, 13 July 2010 (UTC)

- On #4—I don't think it's that unheard of, just not common in American cuisine. See for example steak tartar, yukhoe, other things in Category:Raw beef dishes, Carpaccio, etc. I don't know what the limitations are health-wise in terms of quality, types of animals, etc., or why fish is more common than land animals in this regard (assuming there is reason other than custom). --Mr.98 (talk) 18:15, 13 July 2010 (UTC)

- I would assume that this is mostly about health. It is much more common for parasites and infections to move from one mammal to another mammal than it is for them to move from a fish to a mammal. In general, the more similar the physiology and environment of two species, then also the more likely that they can share parasites / infections. In some cases the risk might be historical than current, but cultural taboos against raw meat persist. For example, trichinella is very rare in the United States today (~25 cases / year), and yet my grandmother still insists that all pork must be thoroughly blackened for safety. Dragons flight (talk) 19:14, 13 July 2010 (UTC)

- on 1: It has to do with the meat juices, which under the heat will be drawn to the surface and ultimately evaporate. If you allow the meat to cool slightly before it is eaten, these juices will make their way back towards the centre of the meat and thus the meat becomes more juicy. 2: Pan-fried trout, which is what I think you're talking about, is delicious, but it usually is fried with the skin still on. 3: never heard of it. With 4, Mr 98 is quite right that red meat can be eaten raw: in these dishes it is usually either cut extremely thinly or pulverised so that an acid (lemon juice) will "cook" the meat. I don't advise eating pork or chicken in this manner, although lamb is delicious as a Carpaccio. 5: both fish have meat which falls into thick slices naturally, though cod is thicker. --TammyMoet (talk) 19:17, 13 July 2010 (UTC)

- (ec) To #1, 'resting' meat serves two purposes. First, it is supposed to allow for the meat to reabsorb some of its juices before you start hacking away at it with a carving knife. Second (and most important) it provides for more even cooking. In the cooking process that you describe above, a piece of meat is pan fried/seared rapidly for a few minutes to create a tasty, browned crust on the exterior. It is then oven roasted for a period of time — several minutes up to a few hours, depending on size.

- Thicker pieces of meat require more cooking time, as it takes longer for the externally applied heat to reach the center of the cut. Even then, remember that the temperature isn't uniform all the way; there will be a temperature gradient through the meat. The outside will be hottest (as it is directly exposed to the hot air in the oven), while the center of the meat will be coolest. At the moment that you take the meat out of the oven, it might well be 'medium' at the surface, but 'rare' at its core. During the ten to twenty minutes (or even more!) of 'resting', the hotter outer layers of the meat will have the chance to transfer some of their heat to the inner parts, while they themselves cool off a bit. The result is that the meat comes to a more uniform temperature – and degree of doneness – throughout. TenOfAllTrades(talk) 19:29, 13 July 2010 (UTC)

- For #2, are you referring to pan-frying or immersion frying? Trout and salmon are rarely deep-fried, but it's not due to the sugar content - it's the fat. Both are very fatty fish and the addition of oily batter just makes it even fattier. Deep-fried salmon also tastes more muted, as if the neutral cooking oil was wiping out the flavour of the fish oil. There may also be problems with poor adhesion of the batter to oilier fish. Matt Deres (talk) 14:38, 14 July 2010 (UTC)

- My take on this is that the temperature of the piece of it evens out and the denatured proteins have a chance to relax and settle back down to some equilibrium. Perhaps this have something similar to the fact that when you prepare a dairy ice cream mix you should ideally let it settle down (preferably overnight) before churning.

- Fried fish is good in a different way than say fried steak. The former has most of the Maillard and caramalization rxns on its batter or coating while the latter has it directly on the meat surface. That being said, pan-frying fish with a very slight addition of sugar is quite fantastic due to the promotion of Maillard type rxns and is indeed practiced in many cuisines. Pan fried meats have a similar enhancement effect when the meat has been treated with sugars.

- Maybe because the colour may bleed across? Try it and see why not, maybe it's one of those silly food myth like that no-cheese-with-seafood-pasta-sauces "rule"

- Yes. Beef carpaccio or tartar can be fun sushi style, but I don't usually eat it due to sanitary risks.

- This may be due to the different amount of connective tissues in different fish types, with some have more collagen between each muscle group (a "flake") than others

-- Sjschen (talk) 21:41, 15 July 2010 (UTC)

Cat vision

[edit]I've read the article Cat, and have learnt that cats don't see red. I'm after more detail, though, and I know their sight is more acute than humans. What frequency ranges do they typically see? I do have a reason for asking this besides curiosity :) --TammyMoet (talk) 18:10, 13 July 2010 (UTC)

- This article The Spectral Sensitivity of Dark- and Light-adapted Cat Retinal Ganglion Cells answers your question. Cuddlyable3 (talk) 18:17, 13 July 2010 (UTC)

- Cool thanks! Wish I could understand it! Joking aside, how does this 510nm peak sensitivity compare with human vision? Does it mean they can see what we know as ultra-violet? --TammyMoet (talk) 19:09, 13 July 2010 (UTC)

- Compare to: File:Cone-fundamentals-with-srgb-spectrum.png. 510nm is green with a tinge of blue. Ariel. (talk) 19:36, 13 July 2010 (UTC)

- Cool thanks! Wish I could understand it! Joking aside, how does this 510nm peak sensitivity compare with human vision? Does it mean they can see what we know as ultra-violet? --TammyMoet (talk) 19:09, 13 July 2010 (UTC)

- Note that the peak sensitivity is the frequency/wavelength at which the sensitivity is highest, not the highest frequency/wavelength at which there is any sensitivity. What the article abstract appears to say is that cats have cones similar to human S and M cones, but there's also evidence of a third cone type in between those (peaking around 520 nm), which was only active in dark (scotopic) conditions. They also have rods similar to human rods, which peak around 500 nm but aren't shown on the image that Ariel linked. That would mean they have color vision similar to a human protanope ("red-blind") in the daytime, but might also have some nighttime color discrimination (unlike humans). -- BenRG (talk) 20:30, 13 July 2010 (UTC)

- There is a difference between not being able to see red and not being able to distinguish red from other colours. As far as I can tell (I can't understand the paper Cuddlyable links to much more than you can), cats can see roughly the same range of wavelengths are we can, but they have slightly different abilities to distinguish certain wavelengths and combinations of wavelengths (for example, humans can't distinguish between yellow light and a combination of red and green light, cat's might be able to, I'm not sure of the details). --Tango (talk) 21:10, 13 July 2010 (UTC)

- The deal is with how many different kinds of color receptor they have. Being sensitive to red - and being able to distinguish red from (say) green are two very different things. Humans have three kinds of color receptor - which are most sensitive to red, green and blue respectively. When we see pure yellow light, both the red and green receptors respond (although less strongly than they do to red and green) - so we can see yellow light, but we can't tell whether it really is yellow (like a yellow sodium street lamp) or whether it's a mixture of red and green (like a picture of a yellow sodium street light displayed on a TV screen). We think TV pictures look realistic because they show pretty much all the colors we can see - but in truth, they aren't.

- Cat's only have two kinds of color receptors - one sees green and the other violet-ish blue. That means that to a cat, red and green look exactly the same. Red and yellow things don't look black (like, for example, infra-red looks to us) - they look green. They may be able to distinguish shades of violet, blue and cyan better than we do (it's hard to tell) - but they are useless at distinguishing orange, yellow and red from green. It's more or less true to say that they are red/green color-blind.

- By contrast, (weirdly) goldfish have amazing color vision - with many more color receptors than us. There are species of shrimp with even better still - some have as many as 14 different color receptors - and for them, the yellow "color" put out by a computer screen would look violently different from the yellow put out by a sodium lamp. Not just a little bit different...consider how much different a frequency that's midway between red and blue (ie, green) looks from a mixture of red+blue to us. For a goldfish, those two kinds of yellow (red+green and halfway-between-red-and-green) probably look as different as magenta (red+blue) and green (halfway between red and blue) looks to us!

- It is widely believed that the reason we are able to see shades of red/yellow/orange/green is because we've evolved to eat fruit - and the difference between an unripe and a ripe fruit is typically some change in color between red (ripe) and green (unripe). Cats are carnivores - and whether that poor little mouse is spurting red, yellow or green blood is of very little concern to them!

- SteveBaker (talk) 14:31, 14 July 2010 (UTC)

- Fascinating fact: from the mantis shrimp article: "[T]he mantis shrimp‘s eye is made up of six rows of specialized ommatidia. Four rows carry 16 differing sorts of photoreceptor pigments, 12 for colour sensitivity, others for colour filtering. ... [I]t can perceive both polarized light, and hyperspectral colour vision [and] permit both serial and parallel analysis of visual stimuli." Those are some serious eyes! – ClockworkSoul 14:09, 15 July 2010 (UTC)

Pressure of Deepwater Horizon Oil Leak

[edit]The Deepwater Horizon Oil Leak is about 1500 m below sea level. At that level, the absolute pressure is about 1.52e7 Pa. Does anyone know what is the pressure of the oil leak? I wonder how the leak is able to overcome the absolute pressure at that level.Inkan1969 (talk) 18:59, 13 July 2010 (UTC)

- The pressure is 4,400psia (absolute psi). Source: [3] (search for "Pressure Data Within BOP"). Ariel. (talk) 19:32, 13 July 2010 (UTC)

- That is roughly 3e7 Pa. Googlemeister (talk) 19:50, 13 July 2010 (UTC)

- You might like the photo of the pressure gauge they are using: [4]. Ariel. (talk) 19:53, 13 July 2010 (UTC)

- Thanks for the picture and the number, Ariel. The picture doesn't correspond to your number though; it reads only 250 psi. Anyway, I see now that the leak can overcome the absolute water pressure as its own pressure is double the value. Inkan1969 (talk) 19:58, 13 July 2010 (UTC)

- It's low because the pipe is open. Once they seal it the pressure will rise. I linked it to show the pressure range they are expecting. Ariel. (talk) 21:08, 13 July 2010 (UTC)

- Thanks for the picture and the number, Ariel. The picture doesn't correspond to your number though; it reads only 250 psi. Anyway, I see now that the leak can overcome the absolute water pressure as its own pressure is double the value. Inkan1969 (talk) 19:58, 13 July 2010 (UTC)

- You might like the photo of the pressure gauge they are using: [4]. Ariel. (talk) 19:53, 13 July 2010 (UTC)

- That is roughly 3e7 Pa. Googlemeister (talk) 19:50, 13 July 2010 (UTC)

- If you follow Ariel's link, you'll see that the pressure at the end of the pipe is only ~2250 psi (15.5 MPa), i.e. only slightly above the pressure of the ambient sea water (at least prior to the capping exercises). This isn't surprising since the flow has been largely unconstrained, so there is no reason for a high pressure to accumulate. One can predict the flow rate from the pressure difference and vice versa. If a 50 cm diameter pipe is belching 50000 barrels a day, then that's less than 1 mph in flow velocity and requires only about 100 Pa of overpressure at the exit. That's actually hardly anything. If it were accessible, a single man with a stout piece of plywood could temporarily block that off. However, that's not the real issue. The oil is being forced out of the ground by the partial weight of the Earth above the oil pocket, and if you attempt to block it, the pressure at the well head will rapidly build. Ariel's link also shows this very well, indicating a pressure in the well bore of 4400 psi, nearly double that of the ambient water. And if one tried to close all of the openings through which oil is currently escaping or being collected, you'd have to be able to resist at least that much pressure and possibly even significantly higher pressures. Dragons flight (talk) 20:19, 13 July 2010 (UTC)

- The leak is 5000' below the surface of the water - but the oil reservoir is 18,000' below that! So the oil is being pushed down on by 18,000 feet of solid rock - creating pressure many times that of the water at 5,000 feet - but when the pipeline between the reservoir and ocean meet, the oil will expand outwards until the pressures are equalized - which is why the pressure gauge is reading so low. However, when the well is capped, the pipe will have to withstand the full pressure of 18,000 feet of rock...and that's the big concern here. If the pipe was weakened or cracked by all the torment it's been through - then capping it could cause it to break in a big way and allow this incredible oil pressure to force it's way out though cracks and fissures in the rock at the sea floor - resulting in a much greater problem. It's frustrating that the process to cap this thing is so slow - but not making matters worse than they already are is a prime concern here. SteveBaker (talk) 13:56, 14 July 2010 (UTC)

- How do you know that most of the weight of the rock above isn't transferred to the rock substrate on either side of the pocket? I have been deep in the earth in a gold mine and in a cave, and in neither case was I under any pressure at all from the many meters of rock and dirt overhead. So it may be incorrect to assume that a pocket of oil 18000 feet below the surface is pressurized by the weight of all the rock. Rock is very good at transferring weight around a void. It is not necessarily a plastic fluid like mud, which would tend to fill voids. If we take the density of rock to be about three times that of water, then the pressure from 18000 feet of rock would be about 24000 pounds per square inch, or 3 times the pressure from a column of water of 18000 feet. How thick would the steel well casing and cap of an ordinary oil well have to be to contain it? Edison (talk) 18:17, 14 July 2010 (UTC)

- Rock and dirt can be self-supporting over relatively small spans (50 to 100 feet maybe) - but this oil reservoir contains billions of gallons of oil. It's gigantic compared to the kinds of cave you've been in - tens to hundreds of kilometers across. Oil reserves aren't exactly like a big cave filled with liquid - they are actually present in sponge-like porous structures with about 60% rock/dirt/sand/mud and 40% oil. So imagine an oil soaked sponge with an anvil placed on top of it and you have the mental model about right. SteveBaker (talk) 23:03, 14 July 2010 (UTC)

- All somewhat plausible, but oil under that much pressure beyond the hydrostatic pressure at the pipe opening should squirt out orders of magnitude faster than was seen. And there must be an impervious hard dome of rock besides fluid sand/mud or the lower density of the oil compared to mud or water would cause it to rise to the surface without any drilling. In other words, it requires a hardrock dome to keep it in. Edison (talk) 03:00, 15 July 2010 (UTC)

- Rock and dirt can be self-supporting over relatively small spans (50 to 100 feet maybe) - but this oil reservoir contains billions of gallons of oil. It's gigantic compared to the kinds of cave you've been in - tens to hundreds of kilometers across. Oil reserves aren't exactly like a big cave filled with liquid - they are actually present in sponge-like porous structures with about 60% rock/dirt/sand/mud and 40% oil. So imagine an oil soaked sponge with an anvil placed on top of it and you have the mental model about right. SteveBaker (talk) 23:03, 14 July 2010 (UTC)

- How do you know that most of the weight of the rock above isn't transferred to the rock substrate on either side of the pocket? I have been deep in the earth in a gold mine and in a cave, and in neither case was I under any pressure at all from the many meters of rock and dirt overhead. So it may be incorrect to assume that a pocket of oil 18000 feet below the surface is pressurized by the weight of all the rock. Rock is very good at transferring weight around a void. It is not necessarily a plastic fluid like mud, which would tend to fill voids. If we take the density of rock to be about three times that of water, then the pressure from 18000 feet of rock would be about 24000 pounds per square inch, or 3 times the pressure from a column of water of 18000 feet. How thick would the steel well casing and cap of an ordinary oil well have to be to contain it? Edison (talk) 18:17, 14 July 2010 (UTC)

Arch

[edit]Why is an inverted caternary the ideal shape for an arch? 74.15.137.192 (talk) 19:16, 13 July 2010 (UTC)

- Have you read our article about inverted catenary arches? It is far from clear that an inverted catenary is "ideal" for arches. — Lomn 19:55, 13 July 2010 (UTC)

- "Hooke discovered that the catenary is the ideal curve for an arch of uniform density and thickness which supports only its own weight."? 74.15.137.192 (talk) 01:56, 14 July 2010 (UTC)

- You have to define "ideal" (Greatest enclosed space? Most pleasing to the eye? Greatest supported load for a given span?) If you keep reading in the inverted catenary arch article to see what "ideal" means in this case: "the [unloaded inverted caternary] arch endures almost pure compression, in which no significant bending moment occurs inside the material. If the arch is made of individual elements (e.g., stones) whose contacting surfaces are perpendicular to the curve of the arch, no significant shear [e.g. slipping] forces are present at these contacting surfaces." The Mathematics Reference Desk might be able to assist you in setting up the appropriate equations to demonstrate this is the case, if you are so interested. -- 174.24.195.56 (talk) 02:48, 14 July 2010 (UTC)

- "Which supports only its own weight" strongly suggests, to me at least, that it's not "ideal" for practical purposes. — Lomn 13:59, 14 July 2010 (UTC)

- "Hooke discovered that the catenary is the ideal curve for an arch of uniform density and thickness which supports only its own weight."? 74.15.137.192 (talk) 01:56, 14 July 2010 (UTC)

The force in walls should go down the walls otherwise it will buckle. A catenary is the shape a uniform chain will take when hung therefore if that shape is inverted the forces will go directly along the line of the chain. Antoni Gaudí used nets with weights attached to design the shapes of the walls for some of his designs - the finished building is then the same shape as the net turned upside down. Dmcq (talk) 10:07, 15 July 2010 (UTC)

- Sorry, why do the forces still go directly along the line when inverted? 74.15.137.192 (talk) 13:45, 15 July 2010 (UTC)

- Because if the force on any little section of strong pulled out of that line, there would be an imbalance between that and the tension in the string (which can't help but run along the length of it). That imbalance would cause the string to move - hence, when friction gradually damps down the motion, the only shape the string can take is one where all of the forces are perfectly balanced and run exactly down the line of the string. Turn this upside down (or just mentally flip the gravitational vector) and you have an arch where all of the forces run down the center of the span...which is (in at least one sense) "perfect". SteveBaker (talk) 20:26, 15 July 2010 (UTC)

animal feelings

[edit]do animals like horses ever get bored? some people say that certain expressions show boredom but others say that theyre not like humans and dont get bored. im stuck!!! —Preceding unsigned comment added by 98.221.179.18 (talk) 20:57, 13 July 2010 (UTC)

- It's a difficult question. Animals certainly have feelings of some kind, but it's hard to say to what extent they are comparable to human feelings. It's a matter of definition, really. Animals kept in captivity in conditions where they have very little stimulation often end up going round and round in circles, which could easily be interpreted as boredom. --Tango (talk) 21:03, 13 July 2010 (UTC)

- My two year old runs around in circles, and loves it. Staecker (talk) 22:24, 13 July 2010 (UTC)

- We can measure levels of anxiety, brain activity, and things like that in animals. Animals without certain types of stimulation can get quite listless and their health can suffer. Some animals (e.g. fish in a tank) don't seem to care very much. You might find Temple Grandin's book Animals in Translation particularly interesting along these lines. --Mr.98 (talk) 21:06, 13 July 2010 (UTC)

- I think it also depends on the intelligence of the animal. I'm fairly sure a chimpanzee or orangutan can get bored, but something like a slug most likely can't. --The High Fin Sperm Whale 21:25, 13 July 2010 (UTC)

- If you've ever been to a zoo where they have panthers in too-small cages, and they pace relentlessly, it's pretty evident that they're not happy. ←Baseball Bugs What's up, Doc? carrots→ 23:05, 13 July 2010 (UTC)

- If you've ever had a dog such as a border collie or Australian shepherd, the answer would be more clear. They need a lot of mental stimulation otherwise they start to act out. Dismas|(talk) 23:20, 13 July 2010 (UTC)

- Animals can certainly display neurological and behavioral problems from a lack of mental stimulation. Whether you can call this "boredom" is perhaps debatable, but the Wikipedia article on Stereotypy#In animals describes some common symptoms in animals from what can be described as "extreme boredom". --Jayron32 23:47, 13 July 2010 (UTC)

- Domesticated animals of many kinds show behavior that's symptomatic of lack of stimulation (which I guess is "boredom"). Dogs chase their tails, parrots pull out their feathers, zoo and farm animals exhibit repetitive behavior, humans get cabin fever. All of these things "go away" when the animal has some kind of stimulation. It's pretty clear though that animals with smaller brains and less active life-styles don't have these problems. Many hunters (like maybe crocodiles) can stay perfectly still for days without evident problems. I suspect the deal is that some animals have evolved to lay in wait - or to conserve energy by staying dormant, where others are 'wired' to use every spare moment of their day productively. This evolutionary trait is what allows some to sit around and do nothing whatever without "getting bored" while the others are likely to suffer mental issues if prevented from doing what their brain chemistry is frantically trying to make them do. SteveBaker (talk) 13:19, 14 July 2010 (UTC)

- u wrote that animals evolve. they dont. they were all created by God in 6 days :)--Horseluv10 (talk) 22:03, 14 July 2010 (UTC)

- Domesticated animals of many kinds show behavior that's symptomatic of lack of stimulation (which I guess is "boredom"). Dogs chase their tails, parrots pull out their feathers, zoo and farm animals exhibit repetitive behavior, humans get cabin fever. All of these things "go away" when the animal has some kind of stimulation. It's pretty clear though that animals with smaller brains and less active life-styles don't have these problems. Many hunters (like maybe crocodiles) can stay perfectly still for days without evident problems. I suspect the deal is that some animals have evolved to lay in wait - or to conserve energy by staying dormant, where others are 'wired' to use every spare moment of their day productively. This evolutionary trait is what allows some to sit around and do nothing whatever without "getting bored" while the others are likely to suffer mental issues if prevented from doing what their brain chemistry is frantically trying to make them do. SteveBaker (talk) 13:19, 14 July 2010 (UTC)

most of the animals I see in the zoo appear very bored and unwell.Fragrantforever 04:24, 14 July 2010 (UTC) —Preceding unsigned comment added by Fragrantforever (talk • contribs)

- And don't let's forget parrots who are very prone to get bored and behave abnormally[5] if not stimulated or kept with a partner. 86.4.183.90 (talk) 07:14, 14 July 2010 (UTC)

- The above answers dealing with caged animals pacing in circles: can someone PLEASE correct the ignorance evident in the explanations for this common phenomenon? 63.17.82.101 (talk) 10:30, 14 July 2010 (UTC)

- Well, you could correct it. What, specifically, do you think is incorrect in the explanations? What evidence do you have for that claim? We're all about dispelling ignorance around here! SteveBaker (talk) 13:41, 14 July 2010 (UTC)

- Yes, horses can get bored. It can result in the problem behavior called cribbing. --Sean 18:56, 14 July 2010 (UTC)

- ignorance??? well, #1 what is scientific about evolution. if you have a bunch of screws and sheetrock will it form a house if u let it sit around for years?? no! its completely unscientific. and #2 how, in the big bang, did the first particle of matter form before the big bang occurred?? things just cant appear! And how can so many accidents happen as to make such a complex and intricate world such as we are living in today? people still dont even understand the human brain completely! are u stumped yet???--Horseluv10 (talk) 01:09, 15 July 2010 (UTC)

- That's an extremely naive view of evolution and you need to stop and think before spouting off whatever your parents or religious leaders are telling you.

- If screws and sheetrock were capable of (a) reproducing, (b) passing on features of parent onto child and (c) mutation - then they would indeed evolve...although not necessarily to form a house! However, since they fail on all three counts so evolutionary theory simply doesn't apply to them. This is not a valid analogy. I might as well say that screws and sheetrock can't have children - and so neither can humans. It's a really dumb analogy!

- Evolutionary theory has been carefully tested using scientific principles - and from everything we have learned as a result, it's extremely scientific...possibly one of the top five most reliable scientific theories we have.

- We don't know how the singularity that started the big bang was formed - but things most certainly can 'just appear'. Read Quantum fluctuation and virtual particle. "Just appearing" is actually one possible way that the universe could have formed.

- The way "so many accidents" could happen is that the universe has been around for 13 billion years and is at least 46 billion light years across. The number of times that something incredible could happen in all of that space and time pretty much guarantees that it will happen. It may be really unlikely that you could roll ten sixes on ten dice in a single roll - but if you keep rolling those same ten dice once every 10 seconds, day and night you'll see it happen about once every 20 years. If everyone in the world rolls ten dice, then it'll happen about 100 times on the very first try. If you wait for 13 billion years and have every cubic centimeter of every planet in the 46 billion-light-year sphere that is the visible universe "roll dice" then once in a while, all of the right chemicals will come together in the right place at the right time to make a teeny-tiny self-replicating molecule. Once you have that, evolution will push things along to where there are complex animals like people.

- But it's even more than that...suppose you have a bucket with 1000 dice in it. The chances of rolling 1000 sixes is so unlikely that you'd never do it even once. But if you were allowed to keep the sixes from each roll then after about 60 rolls - you have all sixes. That's how evolution works. Sure, all of the genes are randomly scrambled - but the good ones, the ones that make animals and plants better at survival are kept and pass on to the next generation. That gradual accumulation of good genes and discarding of bad one is what gets you 1000 sixes. A failure to understand this simple and easy-to-understand thing is at the heart of all of the idiots who don't believe evolution is real. So open your eyes and your brain before opening your mouth.

- SteveBaker (talk) 20:17, 15 July 2010 (UTC)

- That's an extremely naive view of evolution and you need to stop and think before spouting off whatever your parents or religious leaders are telling you.

- ignorance??? well, #1 what is scientific about evolution. if you have a bunch of screws and sheetrock will it form a house if u let it sit around for years?? no! its completely unscientific. and #2 how, in the big bang, did the first particle of matter form before the big bang occurred?? things just cant appear! And how can so many accidents happen as to make such a complex and intricate world such as we are living in today? people still dont even understand the human brain completely! are u stumped yet???--Horseluv10 (talk) 01:09, 15 July 2010 (UTC)

- Yes I stumped what any of this has to do with bored animals. May be you could give me some proof of the relevance? Nil Einne (talk) 14:06, 15 July 2010 (UTC)

the best way to win an argument is to give proof!--Horseluv10 (talk) 12:37, 15 July 2010 (UTC)

- Who is editing someone else's comments now? Acroterion, you are under wikiarrest on this instance of comment removing: [6]. --Chemicalinterest (talk) 01:11, 15 July 2010 (UTC)

- (I have restored the deleted comment. SteveBaker (talk) 19:50, 15 July 2010 (UTC))

- Who is editing someone else's comments now? Acroterion, you are under wikiarrest on this instance of comment removing: [6]. --Chemicalinterest (talk) 01:11, 15 July 2010 (UTC)

- Hey, Horseluv10 is my little sister... Watch it! --Chemicalinterest (talk) 20:32, 15 July 2010 (UTC)

Beware, chemicalinterest is my BIG brother--Horseluv10 (talk) 20:52, 15 July 2010 (UTC)